03 Counting squares

Finding area by counting unit squares

Even though we used the example of a rectangle earlier, the concept of using squares to measure area applies to any shape, including shapes with irregular edges.

Let’s consider the shape shown:

Would you still use squares to measure its area, or would you use an irregular shape like the one shown? The answer is that we still use squares to measure the area, regardless of the shape.

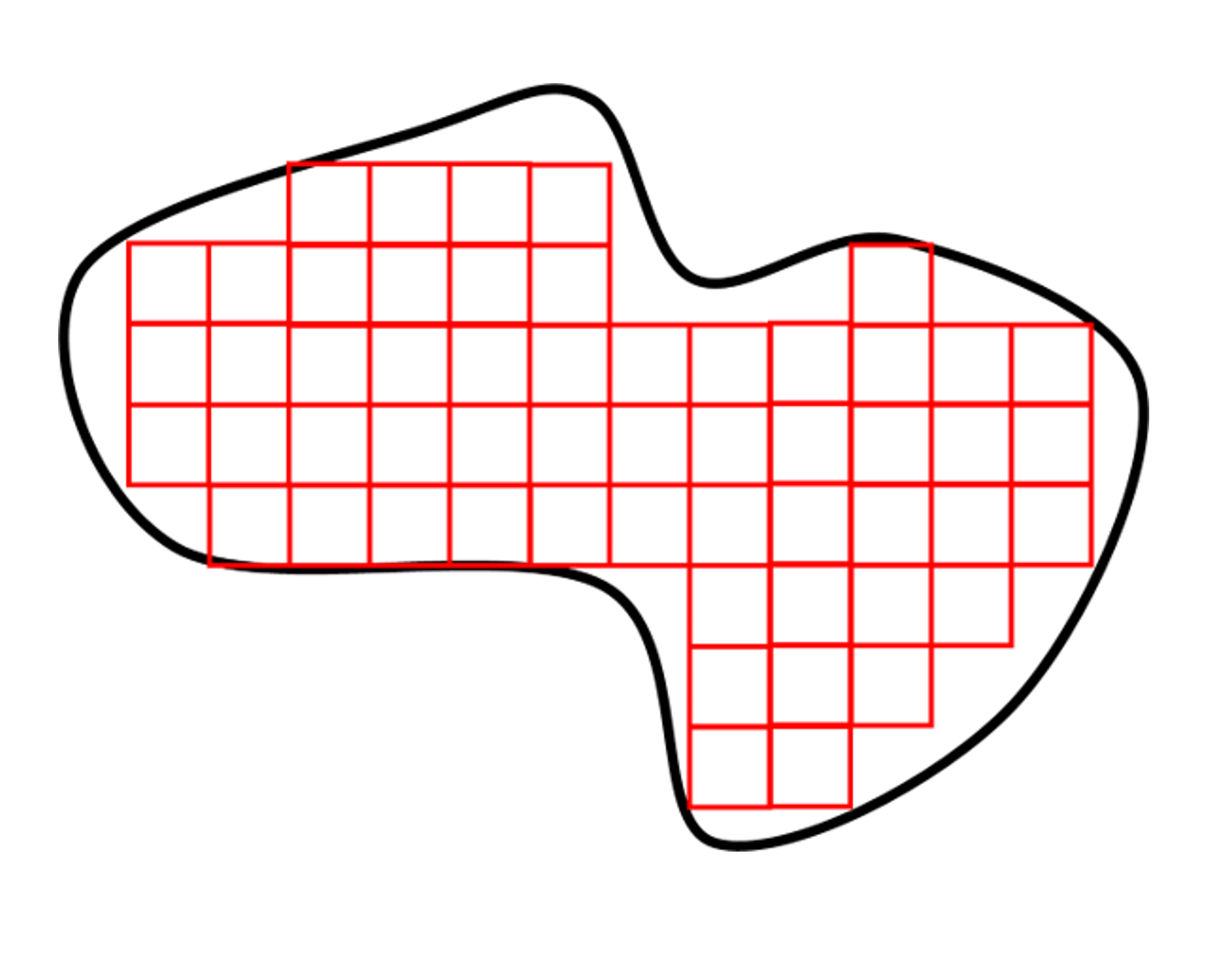

Now, let’s see how many squares fit within the shape in the image given:

Unlike before, we notice that there are some empty spaces without squares, and some squares extend beyond the boundaries of the shape. However, this is not a problem.

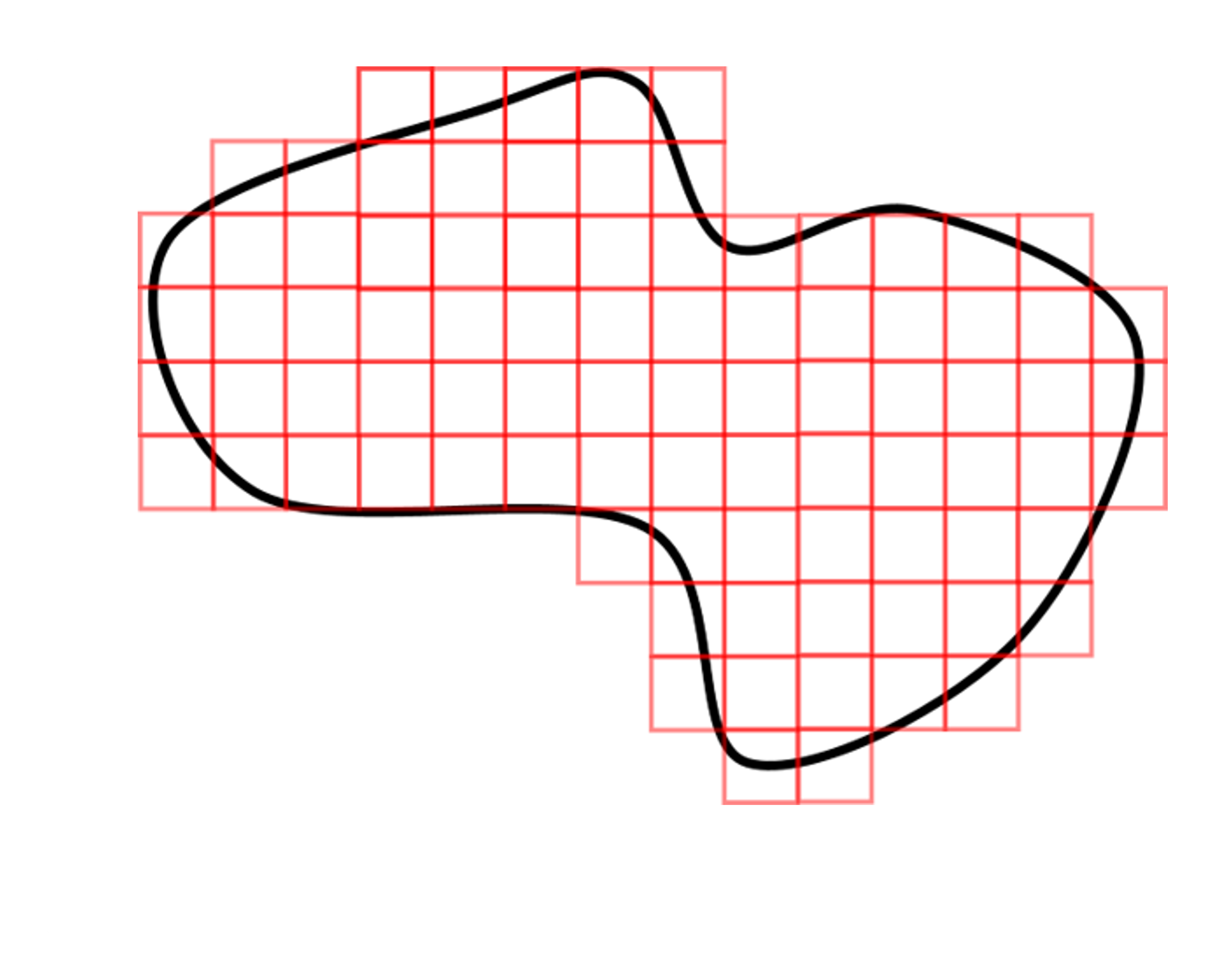

What we can so is to add squares to completely cover the shape, even if some squares extend beyond the outline.

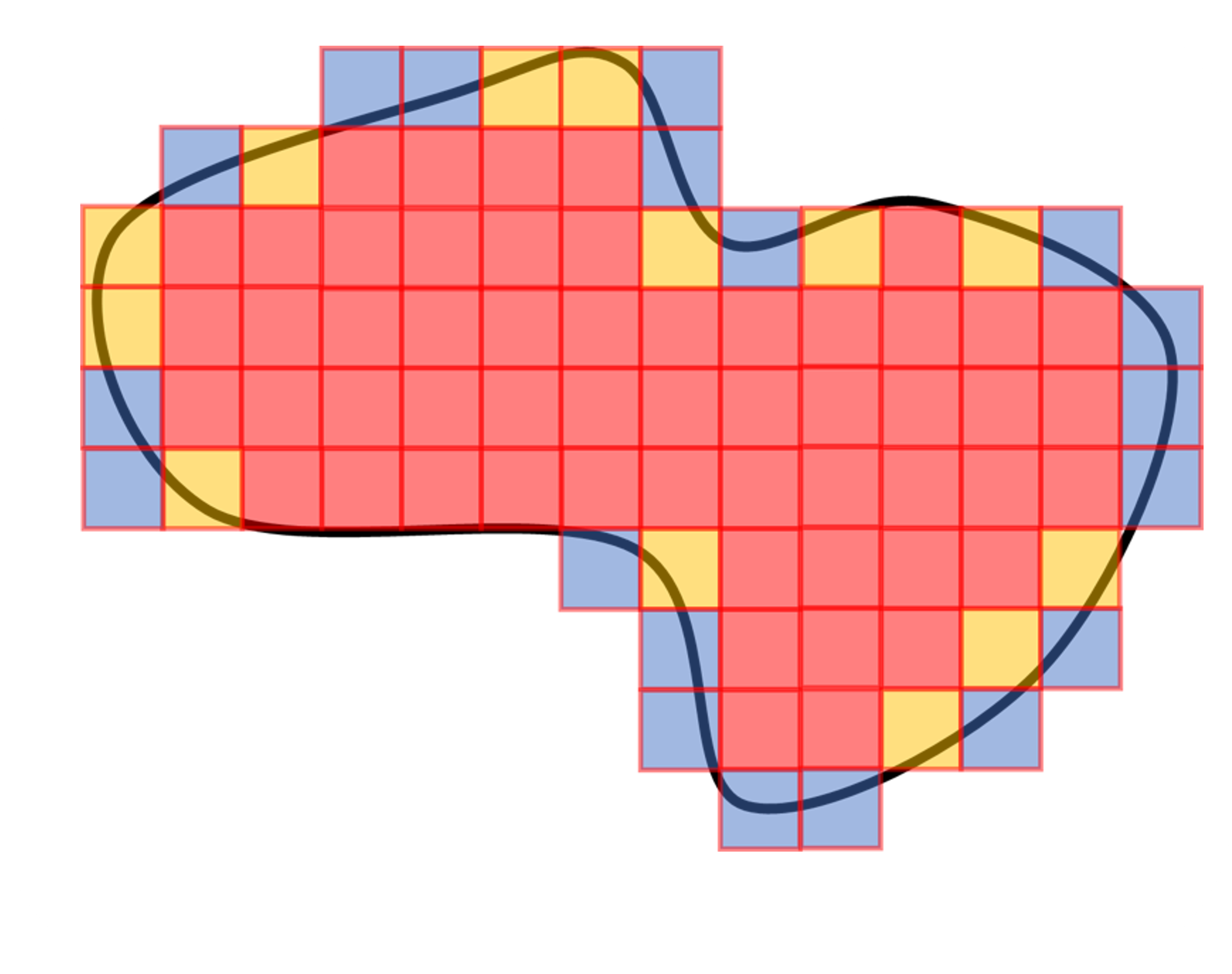

Next, we count all the complete squares inside the shape and also consider squares that are more than half included and less than half included. These squares are highlighted in the image.

In this case, we have 54 complete squares inside the shape (marked in red). There are 13 squares that are more than half included in the shape. Additionally, there are 19 squares that occupy an area of less than half a square unit included in the shape. To estimate the area, we assign values to these squares. We consider the "more than half included" squares to have a value of 0.75 on average, and the "less than half included" squares to have a value of 0.25 on average.

In this case, we have 54 complete squares inside the shape (marked in red). There are 13 squares that are more than half included in the shape. Additionally, there are 19 squares that occupy an area of less than half a square unit included in the shape. To estimate the area, we assign values to these squares. We consider the "more than half included" squares to have a value of 0.75 on average, and the "less than half included" squares to have a value of 0.25 on average.Now, let’s add up the squares with their respective values: 54 + 13 x 0.75 + 19 x 0.25 = 68.5. This gives us an estimate of the area of the shape.

The area occupied by the irregular shape is approximately 68.5 squares or 68.5 square units. It’s important to note that this value may not be completely accurate because the values assigned to incomplete squares (0.25 and 0.75) were estimates rather than exact measurements. Additionally, it’s essential not to forget the unit when expressing measurements, as it specifies the type of quantity being measured. In this case, since we didn’t have a standard unit for the length of the drawn squares, we simply referred to it as 68.5 square units.

While measuring the area of a curved shape requires a bit more effort, the process remains the same. We will explore other types of shapes, such as triangles and parallelograms, and learn how to find their areas later on.

Finding area by decomposition

So far, we have been studying geometric shapes in an abstract context. Now, let’s explore a practical example and learn something new along the way!

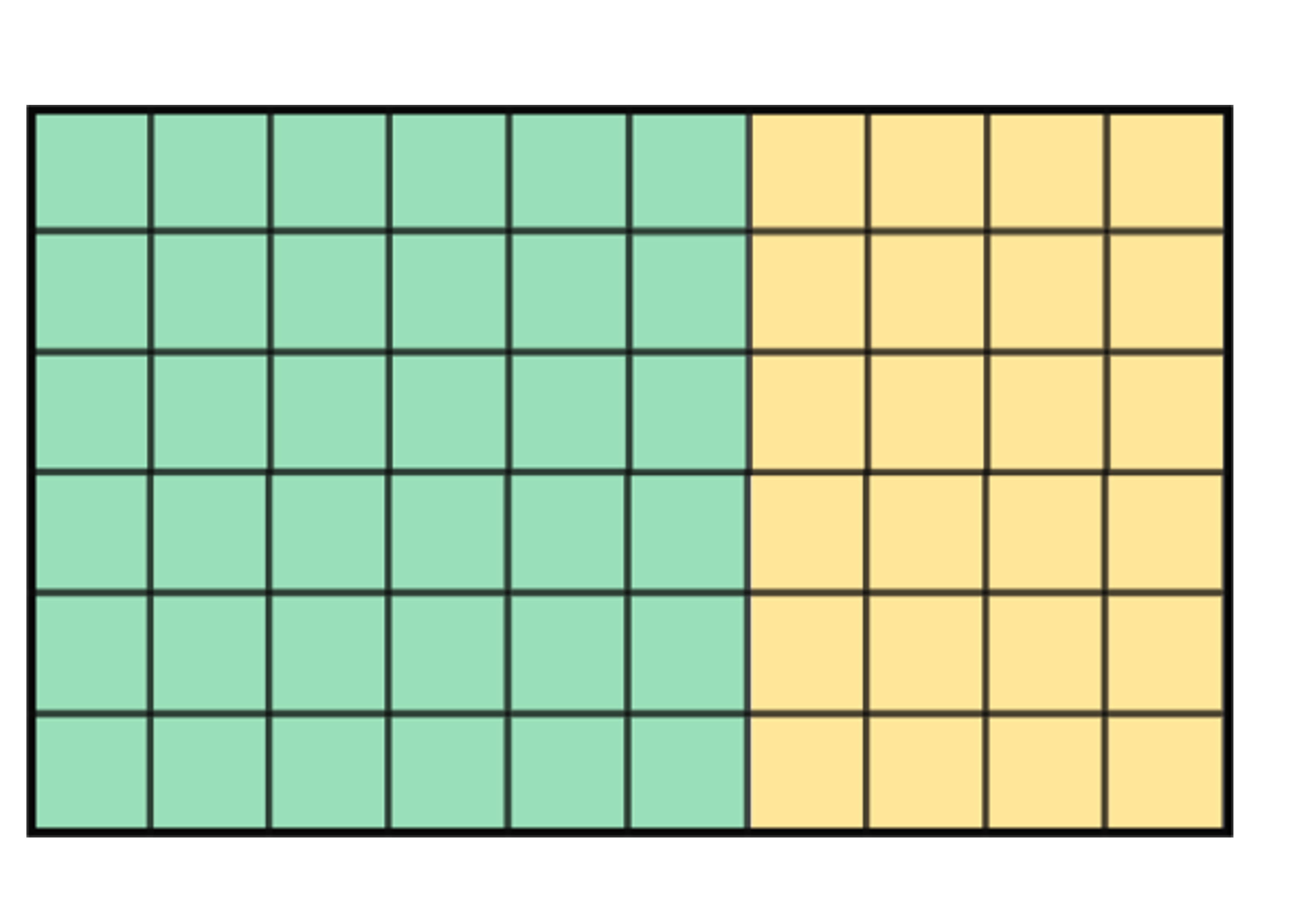

Take a look at the image of a garden. The green area is designated for growing vegetables, while the yellow area is meant for growing flowers. In both areas, squares are displayed, and each square represents 1 square foot in size.

By simply counting the number of squares in each area, we can easily determine the respective areas of the vegetable growing part and the flower growing part.

By simply counting the number of squares in each area, we can easily determine the respective areas of the vegetable growing part and the flower growing part.We can find the area of the garden by adding the areas of the vegetable part and the flower part. Since these two areas together make up the entire garden, adding their respective areas will give us the total area of the garden.

We counted 36 squares of 1 square foot each in the vegetable area, so its area is 36 square feet. The flower growing section has an area of 24 square feet.

To find the total area of the garden, we can count all the squares. It turns out the garden’s area is 60 square feet.

Now, here’s a question for you: Can we find the garden’s area by adding the vegetable area and the flower area together? It seems logical, right? Since these two areas make up the whole garden, if we add their areas, we should get the total garden area.

Let’s use the values we found earlier:

Vegetable area + Flower area = 36 + 24 = 60 square feet. This is the same as the total number of squares that fill the entire garden.

The idea of decomposition is to break down a shape into smaller parts, like we did with the garden to create the vegetable and flower areas. This concept is very useful for finding the area of complex shapes.

When we decompose a shape into smaller parts, it doesn’t change the overall area of the shape. By adding the areas of the smaller parts together, we can find the total area. This is illustrated in the image below.

While this may seem obvious in our previous example, the concept of decomposition becomes particularly helpful when dealing with unusual shapes. We will explore this further later on.

Let’s explore something interesting.

In the image, we have a square, a cat-like shape, and a house-like shape. At first glance, it seems like the house has the smallest area, while the cat has the largest area.

But take a look at the animation given:

Surprisingly, the same pieces are used to create the square, the cat, and the house!

This shows us that even though shapes may appear different, they can actually have the same area if they have been decomposed and rearranged.